[ad_1]

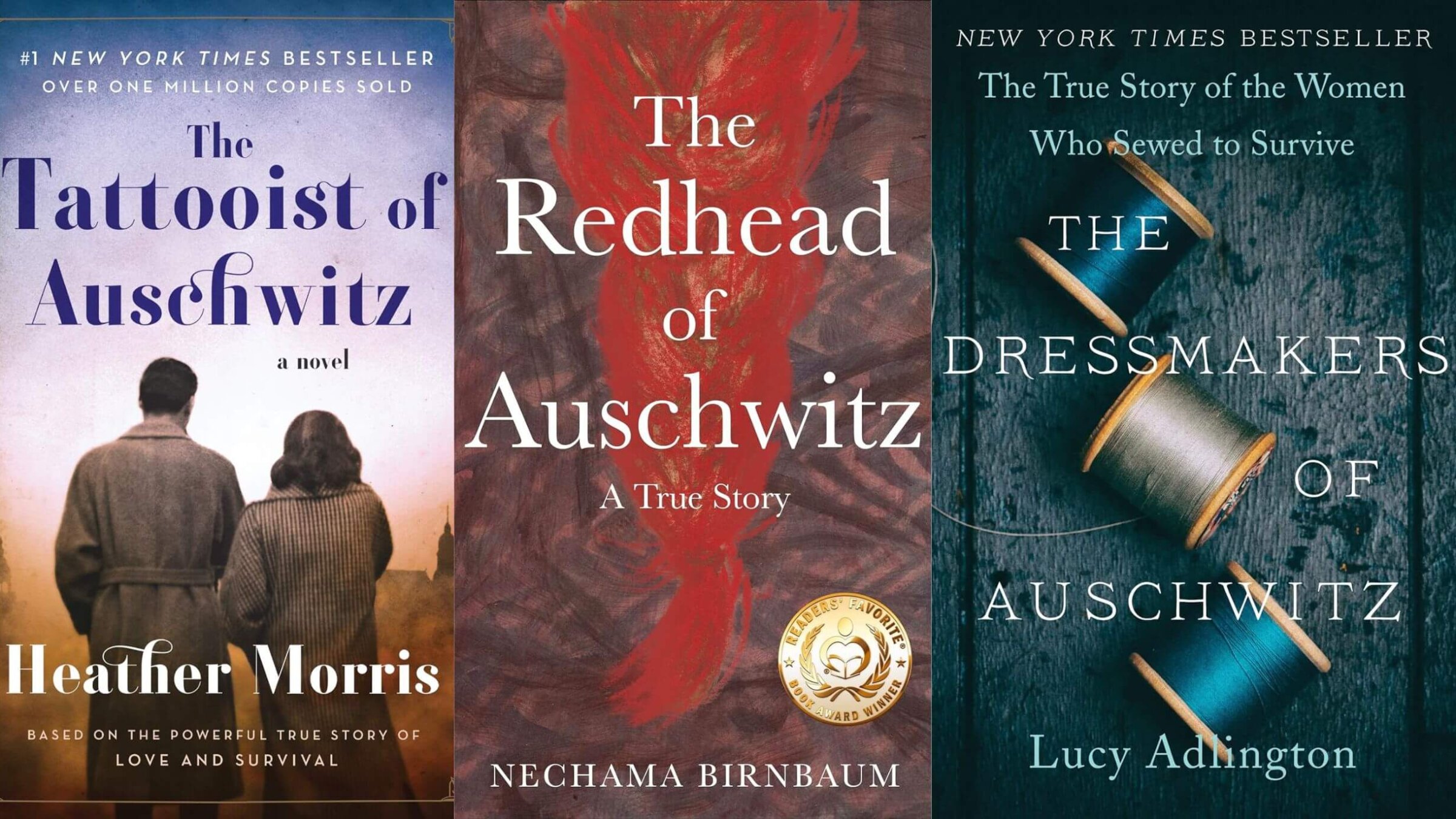

Seeing triple. Courtesy of Harper, Amsterdam Publishers

To the publishing industry:I am begging you, please, to stop publishing books titled The [Blank] of Auschwitz. Truly, seriously: Please.

We’ve had The Tattooist of Auschwitz. The Midwife of Auschwitz. The Violinist of Auschwitz. The Twins of Auschwitz. The Sisters of Auschwitz. The Brothers of Auschwitz. The Daughter of Auschwitz. The Redhead of Auschwitz. The Dressmakers of Auschwitz. The Librarian of Auschwitz. The Stable Boy of Auschwitz. Soon there will be The Ballerina of Auschwitz. It is time to find a template that, to put it baldly, is less annoying.

The framing of all these books commodifies the Shoah, which is both troubling and (at least sometimes) effective: The Tattooist of Auschwitzpublished in 2018, has sold more than 12 million copies worldwide.

But commercial exploitation of the Holocaust isn’t the real issue here: After all, it happens all the time. The bigger problem — for me, personally, as a reader who likes deep, rich and surprising stories about Jewish experience — is that this whole thing risks becoming boring. Please, for the memory of this seismic event, stop making these very individual stories all sound the same.

Some 1.3 million people were deported to Auschwitz throughout the Holocaust. It is no surprise that many diverse types of people — i.e. a librarian, a violinist, a daughter (probably several) — might have been among them. All of their stories surely deserve to be told. But all of their stories were not the same.

And yet, that’s exactly what this insipid title formulation suggests: That all of these stories will be comfortably familiar, containing enough trauma to make readers feel both a little thrilled and a little righteous, and enough hope, or love, or perseverance, or whatever, to leave them feeling good at the end.

There’s nothing wrong with stories that do that. (And far from every story published under this bland title formula follows this schema.) But there is something wrong with the idea that persuasive stories about any given event should match a given blueprint — or at least appear to do so — to be worth reading.

It is very easy, in today’s world, to feel like a serious majority of cultural products we encounter are suspiciously, well, the same. It’s a typical complaint about an entertainment industry that seems increasingly driven by algorithms: If one book, or movie, or TV show of a clear type performs well, the obvious next step must be to make a gajillion more.

In practice, this thinking isn’t as strategically sound as it appears. Few obvious replicas of a blockbuster original ever approach a shadow of that original’s success. A Christmas Prince flew so A Princess for Christmas and Christmas With a Prince: Becoming Royal could flop.

The many [Blank] of Auschwitz books that followed The Tattooist of Auschwitz have occasionally thrown off this rule: The Sisters of Auschwitz, The Daughter of Auschwitz and The Dressmakers of Auschwitz, all works of nonfiction, all spent multiple weeks on The New York Times bestseller list; so did the novel The Librarian of Auschwitz. But a general rule it remains. And what it indicates is that people actually crave things that are new to them.

People read because they want to be in some way entertained or interested; encountering the same thing, over and over again, is a surefire way to produce the opposite result. And people read about the Holocaust, in particular — or, at least, I do — because there is something about it that evades comprehension. The scale so massive; the complicity so emotionally inexplicable; the diversity of the lives disrupted and taken away beyond comprehension. I read about the Holocaust because I want to make the inhuman human — to take the thing so enormous that it would be easier to simply ignore, and access it in a way that actually lets me feel something of what happened.

My annoyance isn’t with the authors of these books, each of whom I think is telling a story that is personally evocative and moving to them. (Those stories, it should be noted, have not always been historically accurate.) It’s with those who have decided that the best way to get these narratives out there is by making them all sound like beach read-appropriate Holocaust-themed clones. I do not like that, when a press release for the inevitable next book in this lineup lands in my inbox, my first reaction is to groan. I care about the act of storytelling, and I don’t like watching myself reflexively dismiss any instance of it because of the few words chosen as a title.

And yet, reflexively dismiss I do. Because the zone has been so flooded with books that sound the same that I now automatically expect everything that comes after them to also sound the same. And thus, perhaps, to actually be the same; and to make the pain of this gigantic and complex atrocity feel a little flatter and a little more palatable; to make it feel more distant, more incomprehensible, even to the extent of appearing unreal.

So join me in saying: Enough is enough. There may have been a xylophonist or taxidermist or antique coin collector or even a granddaughter (yes, really) in Auschwitz, and I might be genuinely interested in their stories. But if you try to sell them to me under the titles we’re both thinking about, I will scream.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and the protests on college campuses.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

[ad_2]

Source link