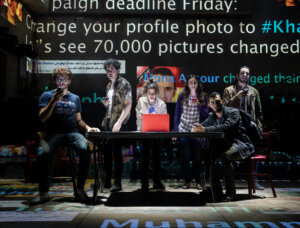

From left to right: Drew Elhamalawy, John El-Jor, Ali Louis Bourzgui, Nadina Hassan, Rotana Tarabzouni and Michael Khalid Karadsheh in We Live in Cairo at

the New York Theatre Workshop Photo by Joan Marcus

There is a song midway through the new musical We Live in Cairo, which follows six American University of Cairo students during the Egyptian Revolution, that clicks with today’s student activists just as much as it did with the students in 2011.

In “Each & Every Name,” the character Fadwa cries for the young people killed in protests against Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak. Palestinian actress Rotana Tarabzoun, wearing a keffiyeh around her neck, delivers an impassioned plea of pain and solidarity. Close your eyes, and this song — with Fadwa’s heavy grief underscored by somber, stringed instruments — could have been the anthem for countless student demonstrations this year mourning civilian deaths in Gaza.

Timeliness is the ingredient that makes We Live in Cairo, now playing at the New York Theatre Workshop, soar. Its themes of youth activism, democracy and hope in the face of despair resonate during a fraught U.S. election year.

In the musical, each student uses a different art form to speak truth to power. For example, Layla (Nadina Hassan) photographs inequality on the streets of Cairo. Amir (Ali Louis Bourzgui) searches for the perfect protest song on the guitar, Orpheus-style. A particular standout in the cast, Karim (John El-Jor), is an outrageous satirist with a biting, Quentin Crisp-esque energy.

As for Daniel and Patrick Lazour, the brothers who wrote the show’s music, book and lyrics? The two have chosen musical theater as their preferred medium for activism.

The Lazour brothers devised the idea for We Live in Cairo while they were both still undergraduate students in Boston and New York. They were inspired by a 2013 photograph published in The New York Times showcasing a group of young Egyptian student activists huddled around a laptop.

In 2017, the Lazours and director Taibi Magar had the chance to visit Cairo themselves. The three read the play in front of activists and American University of Cairo students who had experienced the Tahrir Square demonstrations firsthand.

The Lazours told me they were initially nervous about telling a story that they were not present to witness. The Lazours have Lebanese heritage, and Magar’s father is Egyptian, but they all grew up in America and had never visited Egypt before. But their fears were allayed, they said, when an Egyptian playwright told them, “This is not only Egypt’s revolution. It belongs to the world.”

I spoke to the Lazours and Magar about telling a story about Egypt’s revolution that also “belongs to the world.” They shared how they worked to tell a story authentically grounded in Arab and Egyptian experiences, but also one that extends out to broader audiences — including Jewish New Yorkers — on an East Village stage.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

SAMUEL ELI SHEPHERD: You’ve been working on We Live in Cairo for 11 years now, with productions traveling from Connecticut, to Cairo, to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and now New York City.

In Greek mythology, there’s the idea of “Theseus’ Ship,” a ship keeps being upgraded with new planks of wood that by the end you’re not sure if it’s the same ship you started with, or something entirely new. After all these different productions, do you think We Live in Cairo is still the same play you started with, or has it evolved into an entirely different ship?

PATRICK LAZOUR (book, music, lyrics): I would say it’s the same ship. I don’t think we kept one song from the first draft of the show. Before it was a little bit more of a protagonist-led piece. Now it’s an ensemble piece. But in a lot of ways, the spirit of the show is the same.

Like one of the big things I think about is the idea of fear: how characters deal with activism and the fear surrounding activism. That was sort of disseminated to other characters in the first draft, but now really more elucidated in Layla [the photographer] in this draft.

The idea of showing the humanity of Arab characters, showing a different sort of Arab life, has always been part of our mission. It’s funny because I looked back at one of the first drafts of the show, and I was sort of surprised at how many similarities there were in our first impulses to now.

For Taibi, you’re directing this current production of We Live in Cairo at the New York Theater Workshop: a venue with a history of staging work about countercultures and speaking truth to power. (RENT, Hadestown, etc.) How do you as a director approach telling a story about a real revolution in a space with a history of putting on revolutionary plays?

TAIBI MAGAR (director): The New York Theatre Workshop’s history becomes irrelevant to me as a director on some level. Of course it’s there, but I wanted to be in direct conversation with the piece, and with the history, and with the beautiful work that the Lazours have made.

In terms of what it is to stage a revolution, one of the most beautiful and challenging parts of directing a piece like this is that it’s the story of six beautifully rendered people, but it’s also the story of millions. So I was really conscious, early on, that it had to feel even bigger than the six people.

That was the major impetus for adding projections and for putting the band on stage: just to keep it bigger than them, to keep the outside world around them as full as possible. Otherwise, I think you could make a very hokey mistake thinking like these six people are the ones that overthrew Mubarak, right? As the song “Genealogy of a Revolution” suggests, they infected others.

In the play, every character has their chosen artistic medium used to engage in activism. Musical theater is obviously not as accessible as street art. So why use theatre to tell a story about a people’s revolution?

PATRICK LAZOUR: One thing I always contend with in regards to theater generally – as much as we try to fight against this and as much as I think we’ve made a lot of changes to make theater more accessible – theater is in a lot of ways, especially in New York City, kind of a luxury good.

I think one of our missions in doing this show is getting young people there and making people aware of the $25 Cheaptix that you can get if you’re an artist or if you’re a student, and getting groups there. We’re also doing a lot of community engagement with Arab groups in the city.

On the other end of things, musical theater in terms of content, there’s an experimentalism there, and there’s such an accessibility too: the idea that you have to get your feelings out through song because you can’t get them out through words. A little anecdote, actually! In Tahrir Square, they actually were singing songs from Les Mis.

DANIEL LAZOUR (book, music, lyrics): We really want it to be a safe space for Arab people, Arab activists too, to remind a lot of young people that we’re thinking about this too. By telling the story all in the same room, I think it can bolster them.

This student who I met over the summer, who’s a musical theater writer, who’s now at Columbia, she was involved on campus a lot with demonstrations, and she was like, “It’s wild how the beauty of what was happening on those campuses was distorted.” So many Jewish friends of hers were involved, and it was this beautiful thing that got perverted [in the media]. She came to the show a couple weeks ago and wrote this really amazing email just talking about how it resonates with her and her friends. It was so beautiful to see it resonating with other activists.

When writing a play about any specific cultural group, there is this balance between wanting to authentically write about a specific community and do it justice, and to make sure it appeals to as broad an audience as possible, especially when it’s playing in New York City! (Patrick, we previously talked about this phenomenon in how it relates to Fiddler on the Roof.)

In your different roles, can you tell me how each of you balanced the desire to tell a specific story about Egypt, versus a universal story that everyone can latch onto?

PATRICK LAZOUR: I think it’s actually the opposite of what you think. To tell the universal story you have to get as specific as possible, to try to find authenticity within every single facet of this show.

DANIEL LAZOUR: In terms of getting it right, we’ve been pretty aggressive about sharing it with Egyptians and non-Arabs. It’s sort of dizzying because something that is so blatantly obvious to an Egyptian audience member needs to be explained. It has been a really interesting process of finding what is interesting for both of these groups, and doing what we can to illuminate certain realities.

MAGAR: We put Egyptians first in terms of understanding and appreciating a story and it feeling relevant and speaking truth to our story, and we put Westerners second, and we tried to be radically hospitable to Western audiences with the piece, right? Which is to allow them as many bridges as they’re willing to cross. We weren’t going to make them cross it. But we were gonna extend as much as we can for them to appreciate and understand a culture.

You are writing a story about big themes – democracy, revolution, the power and limits of youth activism – during an election year, and during a period of particularly acute grief within the Arab-American community regarding the wars in Gaza and Lebanon. Are there any lines from the show that you are thinking about during this time?

PATRICK LAZOUR: Are there any lines we’re not thinking about?

MAGAR: “No wind of change, but I can flap my wings.” I love that lyric. It will always feel special.

DANIEL LAZOUR: I’m finding it really interesting that, um, a lot of people are responding to this song in the second act called “King Farouk II.” [A comedic number performed by Karim.] I’m glad people are resonating with it. Maybe it has to do with it being a song about an autocratic despotic leader who just does whatever he wants and resembles someone that we all know very well at this moment. It’s interesting thinking whether if we weren’t in this moment whether this song would land in the way that it is landing.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO