There is good news for anyone who enjoyed the show-stopping aurora borealis last weekend – or missed it: there are almost certainly more on the way.

The huge sunspot cluster that hurled energy and gas towards Earth will rotate back towards us in around two weeks.

Scientists say it will probably still be large and complex enough to generate more explosions that could hit Earth’s magnetic field, creating more Northern Lights.

Since last Saturday, the Sun has continued pumping out increased radiation – a huge solar flare on Tuesday disrupted high-frequency radio communications globally.

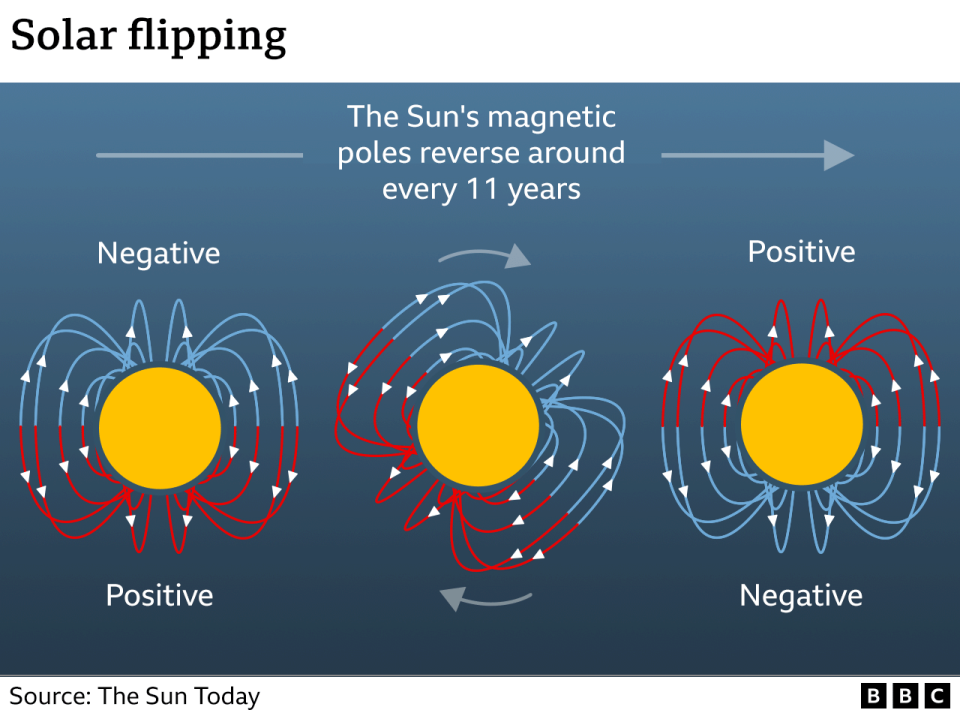

And this hyperactive sunspot won’t be the last. The Sun is approaching what is called “solar maximum” – a point during an 11-year cycle when its activity is strongest.

That happens when the Sun’s magnetic poles flip – a process that creates sunspots that fire out material, generating space weather.

This solar cycle is the 25th since humans started systematically observing sunspots in 1755. It was expected to be quiet, but scientists say it is looking stronger than expected.

The intensity of a cycle is estimated by the number of these sunspots, explains Krista Hammond, a space weather forecaster at the Met Office.

But that doesn’t actually tell us how strong the storms will be when they reach Earth, she says.

The geomagnetic storm last weekend was a one-in-30 year event and the biggest since 2003, says Sean Elvidge, a professor in space environment at the University of Birmingham.

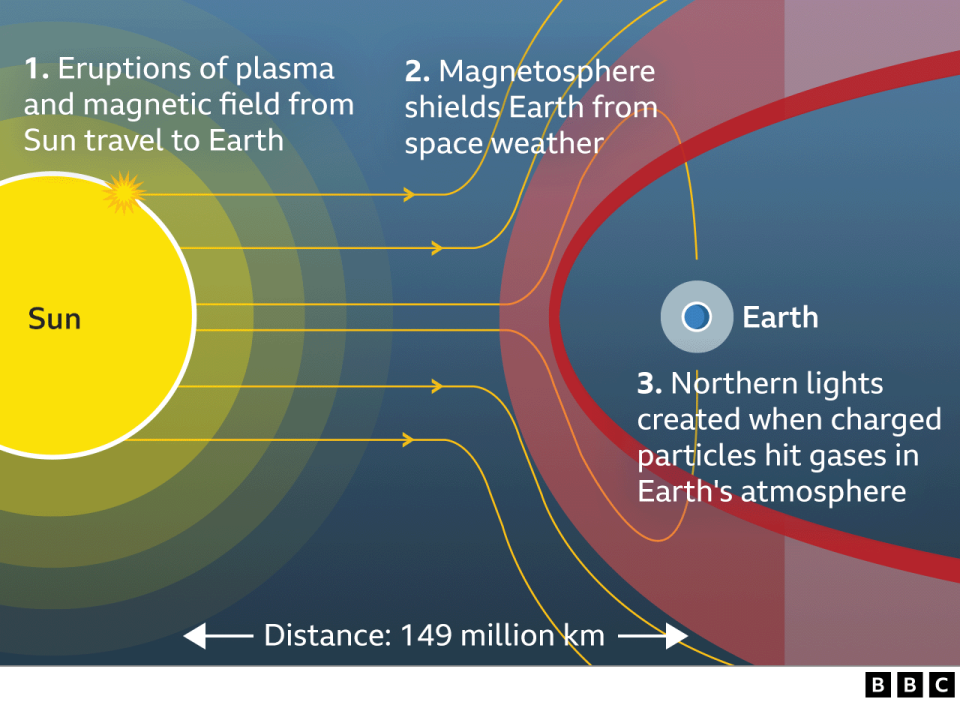

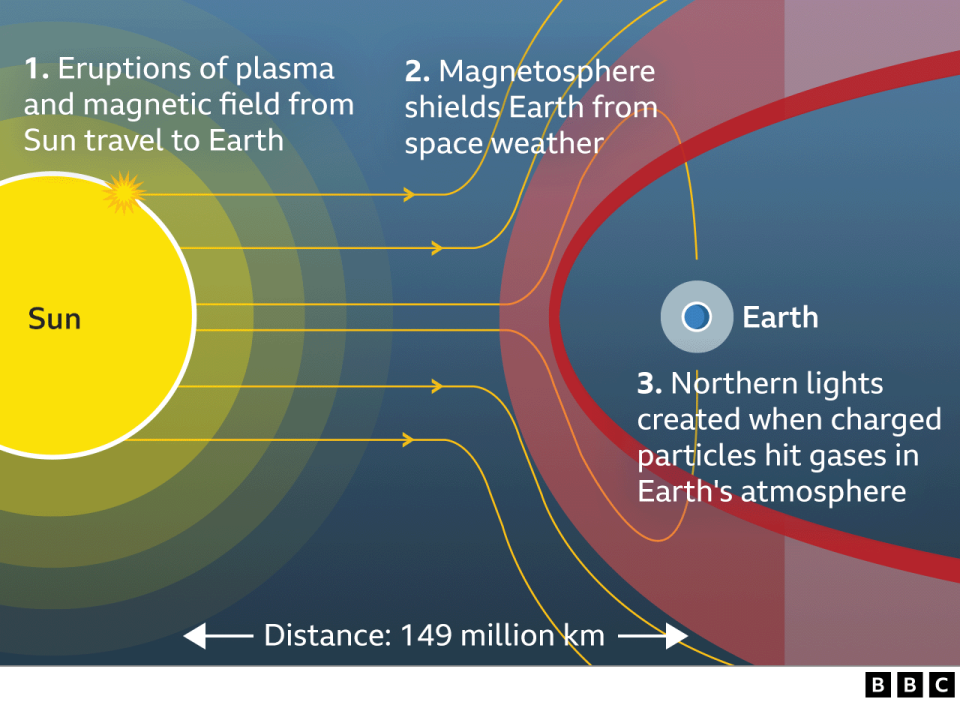

It was caused by at least five coronal mass ejections (CMEs) – eruptions of magnetic fields and solar storms – leaving the Sun in close succession.

They took around 18 hours to reach Earth – where the CMEs interacted with our magnetic field.

This magnetosphere is what shields us from all that immensely powerful radiation – without it, there would be no life on Earth.

The storm turned out to be so powerful it had a G5 alert rating – the highest given by forecasters at the Met Office and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Stories of its impacts on global communications, power grids and GPS have trickled in.

These storms are not just about pretty lights – there is a downside, explains Ian Muirhead, a space systems researcher at University of Manchester:

“We’re much more technologically dependent now than we were even in the last major storm in 2003. A lot of our services come from space – we don’t even realise – it’s the glue that holds together a lot of our economy.”

SpaceX owner Elon Musk said on X, formerly known as Twitter, that the storm put his Starlink satellites that provide internet “under a lot of pressure”. A spokesperson for the European Space Agency (ESA) said the Starlinks had voltage spikes.

Satellites we rely on for GPS and navigation also had signal disturbance as the extra radiation pulsed towards Earth, ESA said.

A flight from San Francisco to Paris was re-routed to avoid flying over the Arctic where radiation was stronger, explains Dr Elvidge.

Farmers who use tractors with high-precision GPS reported being affected, and manufacturer John Deere warned users about outages.

And a satellite operated by UK company Sen that films Earth in high definition was put in an “idle” state for four days, meaning it missed taking images of events like the wildfires in Canada, the company said.

There was stress on power grids too, as the extra current surged through electricity systems.

In New Zealand, which has a similar electricity grid to the UK, the national grid switched off some circuits across the country as a precaution to prevent damage to equipment.

The UK National Grid said there was no impact on electricity transmission. The Energy Networks Association, which represents the UK’s electricity network operators, said it took precautions like ensuring “extra back-up generation to deal with any voltage fluctuations that may occur.”

Space weather is not just a threat remote from us on Earth – something happening out there. The government considers the risks from extreme space weather greater than from earthquakes or wildfires.

On its national risk register, which also covers health pandemics like Covid-19, extreme space weather is rated “four” for likelihood and impact. “One” is for events with the lowest risk, and “five” is the highest.

An extreme space storm – more powerful than the one last weekend – could cause deaths and injuries through power failures, according to the register.

“Mobile back-up power generation would be required in some areas for a sustained period, while damaged electricity transformers are replaced, which could take several months,” it warns.

Power in urban areas could be back within hours, it says, but for people living in remote areas by the sea, it could take months for electricity transformers to be replaced.

The worst-case scenario is what people in the space weather community call a “Carrington-level event”.

They’re talking about a huge solar storm one night in 1859 that saw aurora worldwide so bright that people started to make breakfast because they thought it was daytime.

So much current was generated that telegraph operators in Canada continued transmitting even when they manually disconnected equipment for safety. Fires broke out from damaged equipment.

That same event today could be catastrophic.

“The general consensus is that a solar superstorm is inevitable, a matter not of ‘if’ but ‘when?’,” says a report by the Royal Academy of Engineering.

But we now have two things to help us – forecasting and preparation, explains Dr Elvidge.

Forecasters like Krista Hammond monitor satellites 24 hours a day for solar activity.

They issued alerts to governments and critical infrastructure providers about last weekend’s horde of CMEs heading to Earth hours in advance.

“Our White House situation room is informed about it. Messages come down through our emergency channels down to local governments,” says Shawn Dahl, space weather forecaster at NOAA.

That forecasting and preparation may explain why, despite the doomsday warnings that extreme weather could take out power for days, we actually appear to have seen few obvious impacts of the storm last weekend.

“We are relatively well prepared for these,” explains Mr Muirhead.

Local councils and emergency services test scenarios, including plans to make sure ambulances can still navigate if they lose GPS connection.

But he says the issue of power supply is sensitive, with commercial implications, and companies may not be willing to disclose how much stress was placed on the network.

Space weather forecasting is young compared to atmospheric weather, but as we learn more about the Sun and send more equipment into space, predicting the next superstorm will get closer and closer.