After school on April 15, a fight broke out a couple of blocks from Washington Preparatory High School in South L.A. In a cellphone video of the incident, an adult can be heard saying off camera, just before the fight began: “Let them … fight. If they want to fight, let the … police [inaudible]. … I’m not breaking up s—. I don’t give a f—.”

The adult who apparently declined to intervene was a member of the “safe passages” program designed to make sure students get to and from school unharmed, according to students and a senior union official.

Less than 10 seconds after the fight began, three shots rang out and a student was struck. He collapsed and was pronounced dead at a hospital.

School district officials referred questions about the incident to the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department, which is investigating the shooting, and L.A. Unified provided mixed messages about whether the alleged conduct of the safe-passages staff member was something the district would look into.

The incident in an unincorporated neighborhood near South L.A. is adding fuel to a debate over campus safety in the nation’s second-largest school system and the reduced role of school police. Students and community activists — many of them Black — joined by the leadership of the teachers union, have called for the complete dismantling of the school police department. The presence of any officer on a campus, they say, “criminalizes” students, making them targets for potential harassment and undermining the role of school as a nurturing, academically focused environment.

Schools have responded by increasing their reliance on safe passages, in which district staff, volunteers and hired organizations or companies visibly monitor students’ routes between home and school. These workers are meant to be easily recognized by the yellow jackets or vests they wear.

Increasing numbers of parents, however, especially Latino parents, who make up the vast majority in the school system, want to keep the police. During the wave of Black Lives Matter protests, the Board of Education removed officers from campus — limiting them to patrols, investigations and crisis response — but these parents are demanding their return to on-campus duties. They say that school police make campuses safer and are preferable to relying wholly on city police in emergencies.

The shooting occurred a few blocks from the school, at 108th Street and Western Avenue, where students were milling around a bus stop in front of a convenience store. The Times reviewed two videos of the incident. After the alleged safety team member did not intervene, the videos show a youth rushing in and punching a boy wearing a red and white jacket in the face. At least five boys join in, punching and kicking him, before he pulls out a gun and opens fire.

A few seconds after the shots, a police siren can be heard on the video. One law enforcement source said a school police officer was on patrol about half a block away and probably heard the shots and saw the crowd.

Two 10th-grade witnesses, interviewed by The Times, said they did not hear what the safety team member said; they were out of earshot as they walked down 108th Street to the bus stop. But one of them, who identified herself as Jasmine, said she saw one school safety person in the background “who was just kind of watching it all happen.”

The other 10th-grader, who identified himself as Jahsai, said more than a dozen people seemed to have their cellphones out before the melee started, in apparent anticipation of the fight. He and Jasmine were there only to catch a bus.

Reactions to video

The presence of the safe-passages worker has not been confirmed or denied by the school district. But the common perception among students is that this worker refused to intervene, based on interviews with the two witnesses and about half a dozen other students who were not at the scene.

Nery Paiz, the president of Associated Administrators of Los Angeles, which represents principals and other mid-level managers, said he saw video showing two safe-passages participants who did not step in.

“And you can clearly hear the audio where the person said that he was not going to intervene,” Paiz said. “He said, ‘Let them fight if they want to fight.’ So that’s a problem.”

“We preach to parents — we stress to parents — that we are there and our priority is to the safety of the students, and that incident shows otherwise,” Paiz said.

The school system has said virtually nothing about the incident — twice asserting that the matter had been completely handed over to the Sheriff’s Department. Releases from the department give no indication that detectives are looking into whether adults at the scene intervened to stop the fight.

District officials have refused to say who was responsible for safe passages at the school and how it was organized. A senior district source told The Times that a “vendor” provided the service.

Principal Tony Booker sent out a district-approved message to students and parents, emphasizing that the “incident” occurred “off-campus after school hours.”

“It is with deep sadness that I am calling to inform you of the death of one of our students,” Booker said in the message. “I wish to express our sincere condolences to the student’s family, friends and teachers.”

He added that crisis counselors would be available for students and staff and that “in an abundance of caution, the Los Angeles School Police Department will be providing support to the campus and extra patrols.”

Interim School Police Chief Aaron Pisarzewicz noted at a Monday school safety task force meeting that he had reviewed five cellphone videos of what happened and could not say more because of the ongoing investigation. And Chief of School Operations Andres Chait said, at the same meeting, that it would be standard practice to review any incident with an eye toward assessing and improving procedures.

In a statement, senior district officials declined to respond to questions submitted about the protocols for those involved in safe passages, for example, under what circumstances they are supposed to alert the school police. Nor would they respond to questions about how participants are trained or how they are supposed to deal with fights.

Minimizing police

Washington Prep, like other district high schools, has tried to minimize the presence of police. These officers enter campus only to deal with an emergency.

Schools instead rely increasingly on a counseling-oriented approach that is universally approved of, although not necessarily as a substitute for police. The counseling approach has been hindered by a shortage of social workers and by limited “de-escalation” training for staff. Outside campus, there’s been increasing reliance on safe passages — whose participants can include volunteers or district staff or outside organizations.

Anti-police activists insist that safe-passages programs are the wave of the future: They can provide more block-by-block coverage than one or two patrolling officers — and without the threatening presence, in their view, of armed officers.

School board member Tanya Ortiz Franklin has been the board member most adamant about ending all spending on school police. She said that, in the big picture, reforms are working to make schools safer and improve learning environments.

“Just last week, the board’s School Safety and Climate Committee, which I chair, heard from two of our more than 60 community-based safety partners about their approaches, successes and opportunities for improvement,” she said. “A theme we heard … is that with daily safe passages outside school and peace-building and mentoring inside school, we can prevent a majority of unsafe incidents from occurring in the first place.”

In schools where such practices are well managed, Franklin said, “we are seeing improved relationships and student attendance, and reduced physical altercations.”

Sgt. Jason Muck, the head of the union representing Police Department managers, said the Washington Prep shooting points to a need for consistent de-escalation training. He also called for coordination between the school police and the safe-passages teams.

His view is that some of the safe-passages providers see police as the enemy and are unwilling or unprepared to bring police into a potentially dangerous situation in which the officer could be an ally.

The safe-passages workers, he said, “don’t have walkie-talkies. They don’t have to report things to us. They’re just standing out there. I’m not saying that this still couldn’t have happened with officers there, but trained officers can deal with situations like this.

“From what I’m hearing, this weapon could have been in this student’s possession on campus all week,” he added. “This is stuff that was brewing all week long. And if we had an officer on campus, the officer well could have gotten wind of this and maybe this could have been prevented.”

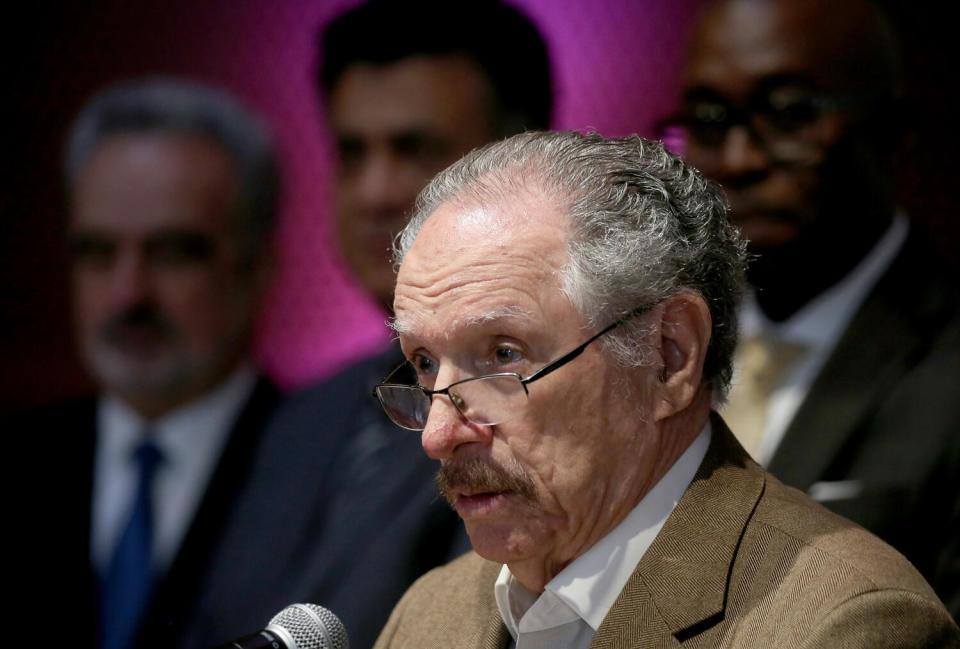

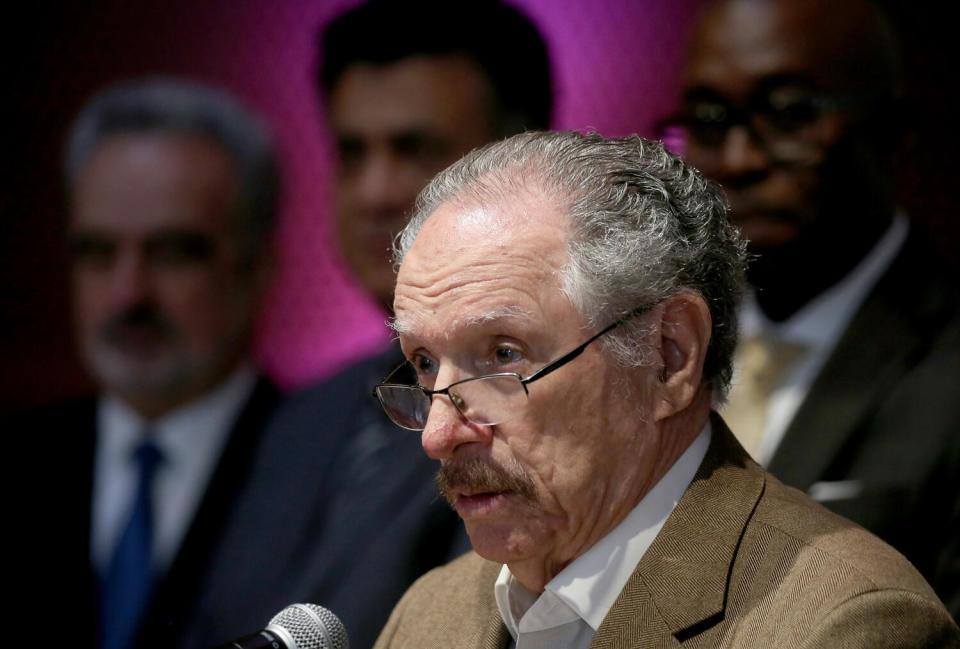

Board member George McKenna, who represents Washingon Prep — and who once gained fame as its hard-charging principal — strongly supports a police presence.

“The only people who are required to break up fights and run to the problem are the school police,” he said.

The campaign against the L.A. school police caught fire in the wake of the 2020 killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis by city police officers — one of a string of high-profile police abuse cases across the country. When the Board of Education majority, in June 2020, ordered officers off campus, they also slashed the school police budget by $25 million — a 35% cut — resulting in reduced services. Before that action, each high school typically had one officer, while two middle schools would share an officer.

The police budget has crept upward since — due to districtwide salary increases and other higher costs — which angered activists who accuse the board of backtracking from commitments to phase out police.

Washington Prep junior Pierre Clark has mixed feelings about safety issues. Those supposed to provide safety were not doing so “if you look in the video,” he said. “They were just standing there watching. I feel like your job is to break up that stuff.”

And at school, “nobody checks you when you walk in. Anybody can walk in there with anything and nobody would know.”

All the same, he has misgivings about a ramped-up police presence: “I want to feel normal. I don’t want to see all these police officers. It’s just a heavy presence, having a lot of cops around you.”

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.