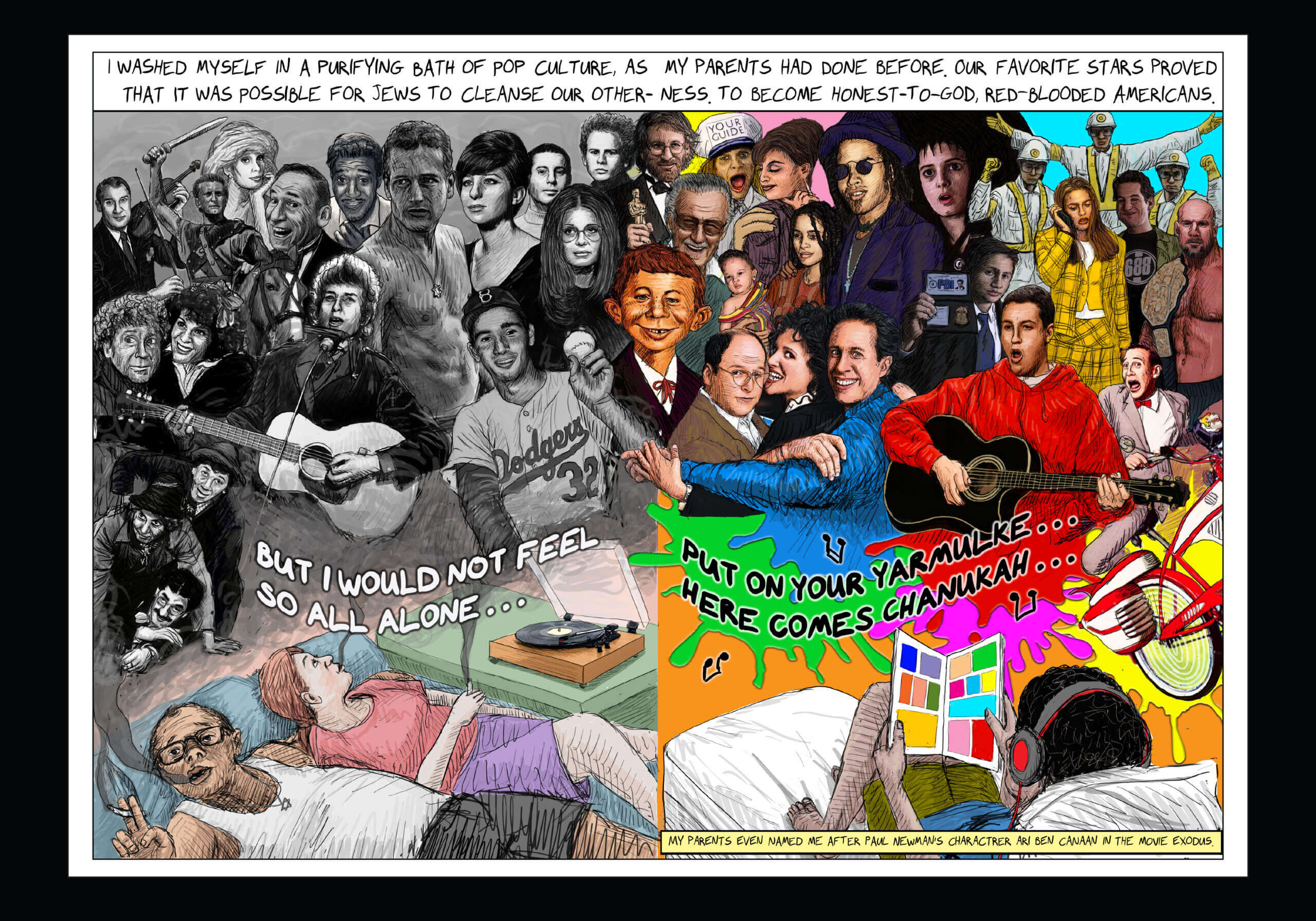

Photo-illustration by L: Ari Richter/Fantagraphics R: Daria Carmon

Ari Richter’s art school professors told him not to make art related to his Jewish identity.

“They not-so-subtly suggested I’d be relegated to Judaica galleries,” said the visual artist, fine arts professor at City University of New York and author of the new graphic memoir Never Again Will I Visit Auschwitz.

Richter, obviously, did not follow his professors’ advice in crafting this chilling, hilarious and affecting memoir of growing up in a family of Holocaust survivors and reckoning with the rise of contemporary fascism. Amid a crowded landscape of literature by Holocaust survivors and their descendants, Never Again Will I Visit Auschwitz stands out for the way in which it relentlessly questions the author’s own assumptions about his family, about memory, and about himself.

“I know they seek absolution,” Richter writes of contemporary Germans he meets on a visit to his relatives’ German hometowns, “and I resent that I offer it by accepting their kindness.”

As mesmerizing as his relatives’ stories are, the most interesting character in the graphic memoir is Richter himself. By letting readers in on his process of researching and illustrating, Richter lets them experience his fears, his ambivalence at making such explicitly Jewish art, and his concerns about the specific ways in which Holocaust memorials encourage remembrance.

The book is anchored by the testimonials of his two grandfathers and one of his great-grandfathers, all Holocaust survivors. As Richter illustrates their harrowing stories of survival — complete with different aesthetic styles to accompany each testimonial — he simultaneously chronicles his fluctuating sense of safety as a Jew in America. Through Richter’s storytelling, we are forced to reckon with all of the intimate details — the desire for vengeance, the joy, the humor — of what it means to inherit the trauma of surviving the Holocaust.

From Tampa to the Tree of Life

Richter was named for Ari Ben Canaan, Paul Newman’s lead character in the film adaptation of Leon Uris’ novel Exodusa strapping Zionist hero who for many embodies the pinnacle of Jewish pride. But as Richter grew up, he felt isolated and embarrassed by his Jewishness as one of the only Jewish students in his Tampa, Florida public school.

He resented being the de facto “Jewish cultural ambassador,” he wrote, a role that his parents seemed to relish with their annual Hanukkah visits to Richter’s public school, performing for his goyishe classmates “the obligatory menorah-dreidel-latke show.”

He coped via assimilation: plunging himself into comic books and crafting an American identity that didn’t center being Jewish. “I washed myself in a purifying bath of pop culture, as my parents had done before,” he writes, above a gorgeous double-spread in the book illustrating a swath of Jews whose fame had transcended their Jewishness: Barbra Streisand, Bob Dylan, the cast of Seinfeld. “Our favorite stars proved that it was possible for Jews to cleanse our otherness. To become honest-to-God, red-blooded Americans.”

For much of his life, Richter said over chocolate chip cookies at Manhattan’s famed Essex Street Market, he believed that he could pass as a non-Jew, “which, my wife constantly tells me, is simply not the case.”

But for him, like many American Jews, things changed after the 2018 Tree of Life synagogue shooting. “I’d had this very clear understanding of where I’d stood positionally, in a security sense, as an American Jew,” he said, “and then the wool was pulled from my eyes.”

He fell into a deep depression, seeing signs of antisemitism everywhere: Jewish cemeteries vandalized with swastikas, visibly Jewish people assaulted in the street, cartoons depicting George Soros as a bloodsucking capitalist manipulating the world. He also began obsessively conducting detailed genealogical research into his family. In the process of accidentally turning into the family historian, Richter learned that he’d lost 45 family members in the Shoah, with at least 31 dying in concentration camps.

Among those who survived, three had documented their experiences.

Stories of survival

In the initial months after the Tree of Life attack, Richter began illustrating a testimonial by his great-grandfather, Richard May, who had been arrested during Kristallnacht and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp.

After the war, he immigrated to the U.S. In 1949, while recovering from a serious heart attack, May typed his story of the Holocaust upon so-called “onion skin,” a translucent paper often used to make duplicates in a typewriter.

Upon his arrival at Buchenwald, he wrote, the detainees were made to run a gauntlet the Nazis dubbed “The Baptism,” full of guards with clubs and mastiffs trained to attack. He was subject to grueling physical labor; those too weak to work were shot and fed to the animals in a small zoo at the camp that the Nazis kept for their own entertainment. Most nights, men attempted suicide by hurling themselves into the electric fences.

Richter had always known parts of this story, but after 2018, “I suddenly had this real urge to visualize it,” he said. When he finished illustrating May’s testimonial, he felt that something “expansive” was happening, and moved on to do the same for his two grandfathers’ stories of survival.

Gradually, Never Again Will I Visit Auschwitz was born. The book is structured around the story of its own creation: As Richter dives into his relatives’ testimonials, he highlights the ambiguity present in their memories, while also exploring how digging into their stories affects his own emotional life — as through the “minor panic attack” he experiences visiting his grandfather Jack’s hometown in Germany, Alsenz, a village where Jack experienced relentless bullying for being Jewish. This meta-narration has a powerful effect: It prompts readers, rather than seeing the Holocaust narratives Richter illustrates as distant stories, to engage with them, experiencing his reactions alongside him.

But it’s not all heavy. Richter chronicles a comically bad visit to Auschwitz, where he is literally herded onto an overcrowded tour bus — “remarkably shitty optics” — and, when trying to order food at the Auschwitz memorial’s cafe, must choose between protein options that all involve pork.

One of the most striking aspects of Never Again Will I Visit Auschwitz is its diversity of aesthetic styles, which help draw out the book’s diverse emotional tenors. Richter depicts his early years in Tampa with a loose, light-hearted touch, emulating the style of a Sunday newspaper comic strip. His great-grandfather May’s violent detainment in Buchenwald is a German Expressionist nightmare. The section about his paternal grandfather, Rabbi Karl Richter, is filled with stills from a testimonial video he made for the USC Shoah Foundation, plus photo collages and illustrated travel documents that echoed the story the rabbi had told at pulpits all around the midwest.

What do we inherit?

Over the course of the memoir, as Richter dives deeper into his family’s history, visiting ancestral sites in Germany and Poland, he wrestles not only with the responsibility of transmitting the story of his family’s survival to his children, but the question of how to best honor this inheritance.

His grandparents had extolled the importance of Jewish continuity, threatening Richter’s parents that to marry someone not Jewish would be to reward Hitler. (“Your grandmother burned in the ovens of Auschwitz, for what?”) In his post-2018 shift to a different understanding of his own Jewishness, Richter’s sense of the value of assimilation changed, too.

He wants his children to live free of the responsibility his grandparents pushed on his parents, but also, he writes, is worried about the possibility of his daughter’s “unique cultural heritage being erased through assimilation into generic American whiteness.”

Navigating this balance is a challenge that, I think, many Jews share: How do we transmit the joys and sorrows of our tradition, without passing on too much trauma? In the end, Richter accepts that his survivor ancestors blessed him with the ability to choose life, and, inherent in that blessing, is the ability to choose the life he wants. He is also under no illusions about how quickly a nation can turn against its Jewish citizens; he and his wife have gotten their children German and Israeli passports, just in case. “But I’ve inherited a certain mentality of optimism to try and continue this generational endeavor,” he said.

“You have to have a little bit of chutzpah to even have a possibility of a future.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and the protests on college campuses.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO