In the early years of the twentieth century, New England was invaded, and towns like Exeter scrambled to fight back.

The invaders were two types of invasive moths – and their caterpillars – that had been accidentally introduced into the region. Both the spongy moth, then called gypsy moth, and the brown-tailed moth were capable of stripping trees season after season, resulting in the death of the tree.

Spongy moths were brought to the United States by Frenchman Etienne Leopold Trouvelot in 1869. Trouvelot planned to crossbreed the moths and create a silk industry in Medford, Massachusetts. The project didn’t work and, unfortunately, the caterpillars escaped. At first, it didn’t seem like much of a problem, and Massachusetts was able to contain the little bugs – for a while. By 1890, the moths were extending their range to western Massachusetts, and by 1900 they had reached Exeter.

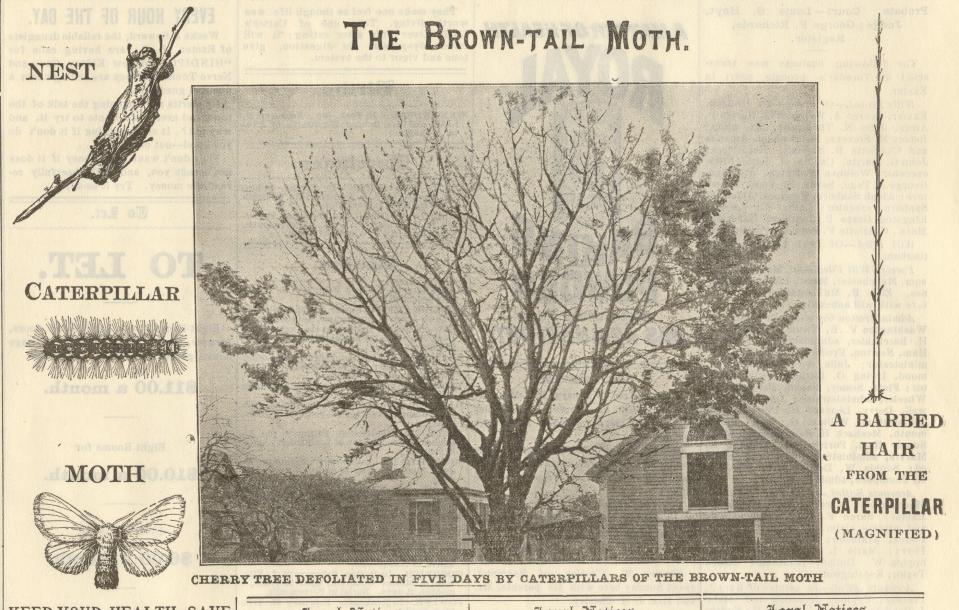

Brown-tailed moths started arriving at roughly the same time. Transported to the U.S. from Europe through the importation of seedlings, brown-tailed moths were more difficult to control and were more hazardous to people than spongy moths. The hairs of brown-tailed moths are barbed and can cause breathing difficulties, rashes, skin irritation and headaches.

The first plan to keep the pests at bay was to contain them. But this didn’t work because transportation had taken leaps forward in the previous decade.

“It is declared, and probably with truth, that the troublesome browntail moth has been carried into New Hampshire by the electric cars, and made a lodgment in Portsmouth, and that automobiles are transferring the gypsy moth into the White Mountain region,” concluded the Exeter News-Letter in June of 1904. Scientists at the University of New Hampshire concurred. Unless everyone stayed at home, the moths were going to spread.

Both moths produce caterpillars that have devastating consequences for trees. These little pests can quickly defoliate entire trees, and their favorite types of trees are those that are indigenous to New England – thus heavily threatening apple and maple syrup production. But it wasn’t just the commercial trees that were in danger. Shade trees such as oak, birch, hickory, chestnut, beech, ash, walnut and elm were also delicious. Actually, looking over the lists of trees, shrubs and vegetation favored by the caterpillars, there isn’t much that would be left over. These bugs were members of the clean plate club.

Historically Speaking: Exeter’s historical trove unveils a WWII coconut

In 1905 – the second year that this was identified as a real problem in town – the Town Improvement Association, a club of sorts, advertised that it, “would pay boys 25 cents a hundred for nests of the brown tail moth until April 1 – the nests to be gathered in the town or immediate vicinity and brought to Mrs. Walker, Court Street, Mrs. John E. Young, High Street or Miss Bell, Front Street.” There, the nests were burned. The boy who brought the most nests would also win an entire new suit of clothes from F.W. Ordway & Company. Apparently, and sadly, it never occurred to the organizers that allowing girls to participate might have doubled the moth army. Tree-climbing girls need not apply.

As enthusiastic as the boys were, some of the nests survived, and caterpillars emerged during the summer months. In September, the News-Letter sadly reported, “It was hoped that the effective work in spring in removing nests of brown-tailed moths would do much to reduce their numbers, but we now find them much more numerous than ever before. Some apple trees have as many as a hundred nests, and on some trees, half the foliage has already been destroyed.”

The only time they weren’t eating was during the bitterest of months in winter. The town encouraged homeowners to remove the nests while it was still cold. The following year, in 1907, the town hired an adult to patrol and cut down nests. Meanwhile, the state of New Hampshire began introducing insect parasites to control the outbreak. Neither proved successful.

In July of 1909, the Exeter News-Letter reported, “The multiplicity and spread of tree pests is becoming a serious matter. The clouds of moths nightly seen indicate an increased number of brown-tails, the removal of whose nests will entail no little labor and expense. The belief is growing that the best way to combat this pest is in its present stage, by means of bonfires, streams of water or otherwise. Thousands, clinging to the walls of Water Street buildings might have been killed during the past week with one’s bare palm.”

Trees were sometimes wrapped in burlap and creosote to stop the caterpillars from climbing up the trunks. These measures, as well as destroying the nests and introducing parasitic enemies were not enough to stop the pests. By 1910, it had been determined that the only way to completely eradicate a colony was to spray the tree with toxic chemicals. The poison of choice was arsenate of lead. If the name sounds terrifying from a public health standpoint, it was. But it was also considered less toxic than its predecessor, Paris Green, which burned the grass when sprayed. Both were discontinued when the modern alternative, DDT, was introduced in the late 1940s.

After spraying was introduced, the infestations were seen only occasionally. Memories of the seemingly biblical plagues remained with people for years.

Barbara Rimkunas is the curator of the Exeter Historical Society. Support the Exeter Historical Society by becoming a member. Join online at www.exeterhistory.org.

This article originally appeared on Portsmouth Herald: Historically Speaking: The moth invasion that threatened Exeter’s trees