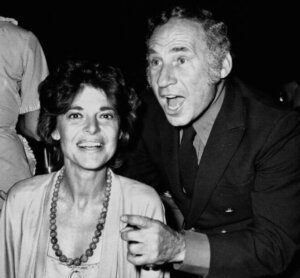

Paul Simon at Chicago’s Auditorium Theatre, circa 1980. Photo by Getty Images

The documentary In Restless Dreams: The Music of Paul Simon takes fans behind the scenes with the great singer-songwriter as his most recent album, Seven Psalms, was being made.

But the two-part, 3 ½-hour film, released earlier this year and now streaming on MGM+also tells Simon’s life story, weaving together footage of past interviews and performances with his reflections on what it all means now.

And while Simon, now 82, has never been one to parade his Jewishness, the film is loaded with Jewish references. Here are some of those moments from the film, plus a few delicious asides about his childhood in Queens, his political awakening and the evolution of his career.

The culture of Queens

Growing up in Queens in the 1940s and ’50s, Simon recalled in the film, “my culture was the radio. It wasn’t like I sang the music of Queens. We didn’t have people sitting around on the porches in Queens singing fables about what it was like in Queens in the old days. There was none of that.”

But apparently being from Queens wasn’t quite exotic enough when American Bandstand host Dick Clark asked where Simon was from. Simon, 16 at the time, put on a Southern accent and responded, “Macon, Georgia.” (His childhood friend and singing partner, Art Garfunkel, said, “Queens.”)

From his house in Forest Hills, it took Simon an hour each way by bus to get to a record store in Jamaica, Queens. After making the trek to buy the Everly Brothers’ “Bye Bye Love,” he accidentally scratched the record, decided he couldn’t live without a pristine copy, and took the bus to the record store all over again.

‘Ethnic’ names

Simon had four idols growing up: John F. Kennedy, Yankees baseball star Mickey Mantle, comedian Lenny Bruce, and Elvis Presley, who Simon said had “one of the weirdest names I ever heard. Everybody that I knew was named David Rothbaum or something.”

He and Garfunkel recorded their first hit, “Hey Schoolgirl,” in 1957, performing under the names Tom & Jerry. But Simon said there was a “big debate” about what names to use for their 1963 debut album, Wednesday Morning 3 A.M. Another duo was already performing as Art and Paul. One idea was “The Rye Catchers,” because, Simon said, they were seen as “Salinger-esque.”

Finally, Columbia Records president Goddard Lieberson decided on Simon & Garfunkel, “which at the time was a pretty radical thing to have ethnic names,” Simon said. Performers were still anglicizing their names in that era — Bob Zimmerman as Bob Dylan, Francis Avallone as Frankie Avalon — so “this was a big deal. Goddard Lieberson was definitely making a statement.”

Mentored by a Jewish refugee

Simon spent the next two years in England, without Garfunkel, playing small venues: “These weren’t clubs like New York clubs; these were a room above a pub. There might be a microphone or maybe there wasn’t.”

A woman named Judith Piepe who came to all his shows took him under her wing and helped promote him. “She was a refugee from Germany,” Simon said. “Her father was a Communist. She was Jewish. She fled during the war. She converted to the Anglican church.” She gave him a room to live in in her East End flat down by the docks and put him on her radio show on the BBC.

Political awakening

Looking back on his early years with Garfunkel, Simon said, “we were never part of any of the movements. We were not known as political people. We were not known as drug people. There was a fair amount of criticism that thought we were really square and corny.”

Performing at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival, Simon recalled being shocked watching The Who smash their guitars onstage. “It made me cringe,” he said. “I used to think, God, when I was a kid, I had to save up so much to buy a guitar!”

Simon also described the duo’s political awakening as riots engulfed cities, the Vietnam War raged and leaders were assassinated. In 1969, when they were offered a TV special, “we decided the show would have a political idea. We didn’t go in there looking for a fight. We thought we were expressing the simple truth of what’s going on.”

He soon realized “just how naive we were — we thought everybody was a liberal.” When they proposed debuting Bridge Over Troubled Water over footage of JFK, Bobby Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the producer said, “‘You can’t just have those three.’ And we said, ‘Why?’ And they said, ‘Well, they’re all Democrats.’ And we said, ‘Really? We think of them as all assassinated.’”

Freud, Mel Brooks and Carrie Fisher

Many segments of In Restless Dreams — perhaps too many — analyze Simon’s breakup with Garfunkel. From Simon’s perspective, Garfunkel’s vocals and harmonies for songs that Simon was 100% responsible for writing were not enough reason to keep the relationship going — especially after Garfunkel began to pursue an acting career, performing in the movies Catch-22 and Carnal Knowledge. Reflecting on his anger over Garfunkel prioritizing Hollywood over making records, along with the false impression fans had that Garfunkel was his co-writer, Simon said: “Maybe it was my perfect Freudian trauma that my mother said to me once, ‘You have a good voice, Paul, but Arthur has a fine voice.’”

Their last album together was Bridge Over Troubled Waterbut before that, the song “Mrs. Robinson” became a hit from the soundtrack for The Graduate. That iconic Mike Nichols film starred Dustin Hoffman as a college grad seduced by an older woman played by Anne Bancroft.

“I ran into Mel Brooks the other day,” Simon told a TV interviewer around the time the movie came out. “I had no idea how miserable that song had made his life.” Brooks was married to Anne Bancroft, so everywhere they went, people started singing, “Here’s to you, Mrs. Robinson.”

Much of the documentary chronicles Simon’s solo career, including his many appearances on Saturday Night Live and his fascination with world music. The sounds he encountered in South Africa and Brazil made Graceland and The Rhythm of the Saints different from anything else he’d done — and from anything else in pop music at the time. But his forays in South Africa in the apartheid era were controversial. The documentary takes pains to justify his work there as a way to promote Black musicians in South Africa and those in exile like Hugh Masekela.

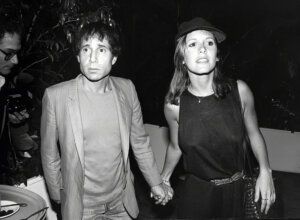

There’s also a segment in the film on his brief, unhappy marriage to actress Carrie Fisher, whose father, singer Eddie Fisher, was Jewish. Simon’s song “Hearts and Bones” includes a rare explicit Jewish reference as he describes himself and Fisher as “one and one-half wandering Jews / Returned to their natural coasts / To resume old acquaintances and step out occasionally / And speculate who had been damaged the most.”

A debate on belief

The film’s retrospective segments are punctuated by scenes of the real-time production of Seven Psalms. The album originated with a dream Simon had that was “so strong” he woke up and wrote it down. Simon described the process of turning that dream into an album as deeply spiritual, but also beset with challenges: He lost his hearing in one ear as the album was underway and struggled at times to hear and sing notes precisely.

He framed that struggle in near-religious terms, like a God-given test from the Old Testament: “I began to think, you know, this whole piece, it was actually something I was meant to grapple with, and maybe this hearing is part of the process and it was going to be harder now and maybe it was meant to be harder.”

In one song from Seven Psalmshe sings, “The Lord is my engineer … the path I slip and slide on.” In another, he sings, “I have my reasons to doubt,” a line that he says describes “a debate” about faith: “Oh, OK, I believe. Oh, I don’t know, maybe I don’t.”

That yearning and uncertainty may remind longtime fans of the existential sentiments expressed so eloquently in Simon’s early work — lyrics like, “I’m empty and aching and I don’t know why,” from “America,” or the melancholy line from “The Sound of Silence” that inspired the documentary’s title: “In restless dreams I walk alone.”

What is the meaning of life, those songs seemed to ask, and why do I feel so lost? Perhaps Simon’s musings about Seven Psalms provide a partial answer to those questions, while at the same time suggesting that his search for meaning has taken a religious turn.

“This is a journey for me to complete,” he said. “This whole piece is really an argument I’m having with myself about belief — or not.”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and the protests on college campuses.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO