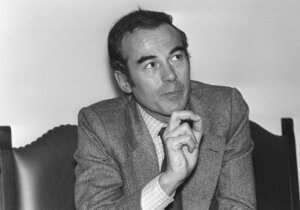

Robert Badinter with Emmanuel Macron (L) at the commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the abolition of the death penalty in France. Photo by Getty Images

In 2022, a frail but fierce Frenchman threw down a gauntlet before the state of Texas. In a video produced by Ensemble contre la peine de mort, a French organization opposed to the death penalty, the man demanded that Texas authorities save the life of Melissa Lucio, who despite several glaring irregularities in her trial, had been condemned to death in 2008 by a Texas jury for the death of her two-year old child. Failure to do so, he declared, “would be a sacrilege and, I must say at the end of my own life, a revolting injustice that would dishonor the state of Texas.”

Melissa Lucio still waits on death row for the Texas courts to decide her fate. Last Friday, however, Robert Badinter, the speaker in the video, died in Paris at the age of 95. I suspect that few of my fellow Texans heard his words two years ago, much less news of his death two days ago. But if they did listen to the short clip, they would have been struck by the way Badinter utters, with scarcely suppressed indignation, “déshonorait.”

Yet, the particular emphasis Badinter gives the word “honor” would not surprise the millions of French whose country has been shaped for the better by one of their country’s most consequential and admirable public servants. Whether as the minister of justice in the 1980s who oversaw the abolition of the death penalty, or as the president of the country’s Supreme Court in the 1990s, who established the court as a true equal to the other branches of government, or as the advocate of the Enlightenment ideals and adversary of state-sanctioned murder, Badinter’s fidelity to revolutionary France’s trio of values — liberty, equality, and fraternity — never faltered.

This deep emotional and intellectual attachment came naturally to the son of Simon Badinter who, in 1919, fled the antisemitic violence of his native Bessarabia (present-day Moldova) for France. Where else could he find a safer haven? Badinter often quoted the father of the French Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas who, during the Dreyfus Affair, concluded that “a country tearing itself apart over a single Jewish officer is the country where I need to live.”

Yet France was also the country from which Simon Badinter, two decades later, was deported and murdered at Sobibor in 1942. The adolescent son was, as one obituary suggested, forever marked by his father’s love of the French Republic, but no doubt also by the shock of the persecution of French Jews by the collaborationist and antisemitic Vichy regime. For these reasons, perhaps, Badinter insisted that France was not the “homeland of the rights of man, but instead was “the homeland of the Declaration of the Rights of Man.” That extra word is crucial. It is never enough to declare these universal rights, in short, but instead it is always necessary to also defend and extend those rights.

This was the ethical and historical imperative that led Badinter, upon taking office as the garde des sceaux, the Keeper of the Seals or Minister of Justice under President François Mitterrand, to fight for the abolition of the death penalty in France. When still a practicing lawyer, Badinter took the case of Patrick Henry, guilty of killing a child he had kidnapped. Badinter did so for the most obvious and most difficult of reasons: the commandment “Thou shalt not kill” must apply to one and all no matter what they have done and no matter what the state’s justifications are. “Do not believe you are defending society by this bloody means,” he told the jurors in his reference to the guillotine. “If you cut that man in two, you will dissuade no one.”

A few years later, when Badinter made his case in front of the National Assembly for the practice’s abolition, he spoke for nearly two hours. He knew that a substantial majority of the French still supported the death penalty, just as he knew there would be attacks and insults from the opposition parties. And yet, in videos of the event, he appears less a government minister and more a biblical prophet. At a key moment, Badinter looks up from lectern and looks directly at the gathered representatives of the nation: “The question that we face, as we all know, is political and especially moral.” With these words, the chamber fell silent.

Whereas abolition is the rule nearly everywhere among free countries, Badinter observed, in dictatorial countries the death penalty is everywhere practiced. “This is not a simple coincidence, but instead a correlation. The death penalty’s true significance comes from the idea that the state has the right to dispose of a citizen, even to the point of taking their life. This is why this penalty is part and parcel of totalitarian systems.” (Or for that matter, part and parcel of democratic states in our country where Republicans, and not republicans, hold super-majorities as they do in Texas.) Badinter concluded his speech by declaring “Tomorrow, thanks to each of you, we will no longer share the shame of furtive executions at dawn in French prisons. Tomorrow, the bloody pages of our history will have been turned.”

So many other pages of French and European history, from the abolition of the crime of homosexuality to the founding of the International Criminal Court, have also been written in large part by Badinter. Above and beyond these accomplishments, however, was Badinter’s greatest achievement: to live a public life that resisted the cruelty and coarsening of our era and reflected the moral values of a man who always proudly identified himself as “republican, secular, and Jewish.”