If you were paying attention to the news in the early 2000s, you’ve likely seen footage — desperate parents, exhausted and frightened by their troubled teen’s behaviour, pay to have their child abducted in the night and placed in a program that will scare them straight and reform them back into good behaviour.

Netflix’s latest docuseries offering, The Program: Cons, Cults and Kidnapping, takes a harrowing look at what happened to one set of such teenagers, who underwent a personal nightmare when the institution they were placed in ended up being, essentially, a corrupt machine for torture, brainwashing and abuse.

The three-part documentary, which began airing Mar. 5, focuses on the story of Katherine Kubler, who also serves as director for the series.

In the early 2000s, at the age of 16, Kubler was attending a Christian boarding school in Long Island, N.Y., when she was expelled for drinking hard lemonade. Staff at the school said her dad would arrive soon to take her home, but, instead, two strange men with handcuffs showed up to take her away.

They forcibly escorted her to the Academy at Ivy Ridge in upstate New York — a facility that was peddled to her parents with a shiny brochure and slick video featuring kids riding horseback and swimming in a lake — where she faced anything but the idyllic image that was sold to her family.

Instead, she was enlisted in a program that forced compliance through manipulation, fear and violence. She was made to follow dozens of pages of rules, that included draconian instructions like “no looking out the window,” “no talking,” “no making eye contact,” and “all bathroom visits are to be monitored, with the door to the stall left open and a staffer present.”

Ivy Ridge billed itself as a boarding school offering a structured environment for troubled teens, with the goal of helping them address their behavioural, emotional and academic issues.

But, as the docuseries explores, it was a much more sinister facility that lead to the traumatization of hundreds of teenagers in its eight years of operation — much of it happening without the teens’ well-intended parents having any idea, and even facing an element of brainwashing themselves.

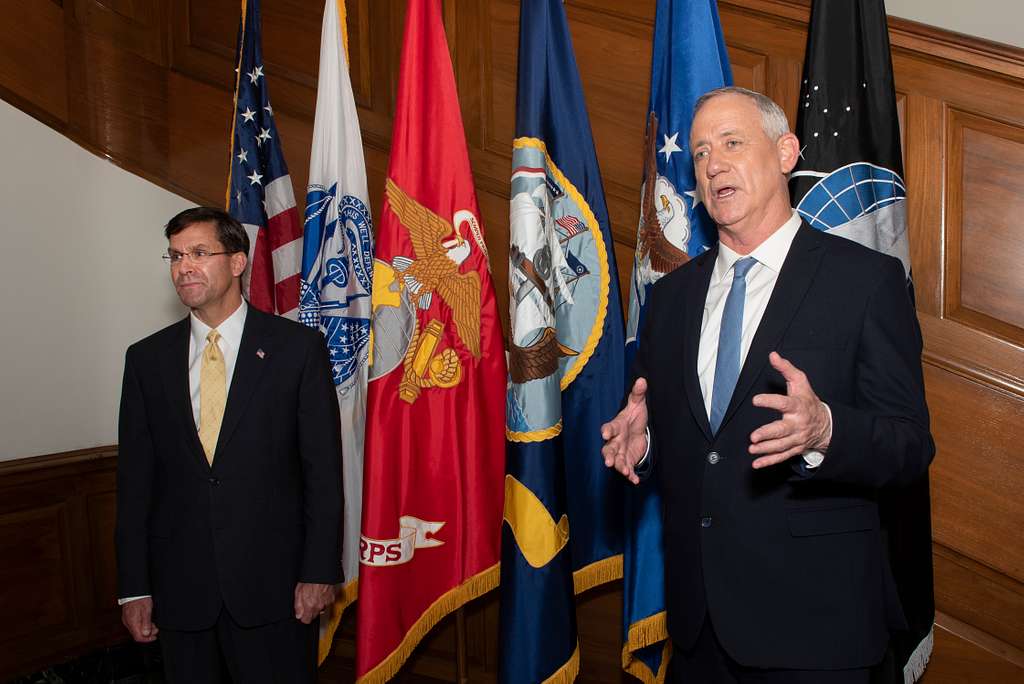

Survivors of Ivy Ridge pose for a photo inside the abandoned school.

Netflix

The hunt for revenge

There’s no doubt about it — Kubler is out for revenge with this docuseries, something she directly acknowledges to the camera.

“I’ve always said this was like Count of Monte Cristo because I had this false imprisonment where I planned my big revenge,” Kubler says to the camera, standing in the now-dilapidated library of the abandoned facility. “I was like, ‘When I get out of here, I’m going to make a documentary about these places, and I’ll get back at every one of you!’”

Kubler and a handful of other Ivy Ridge alumni act as an amateur investigators, set out to expose the truth of the suffering they endured. They speak to the facility’s former staff, academics who studied cults and manipulation, and attempt to follow the paper trail of what remains a lucrative, billion dollar industry.

An auspicious finding, in the form of hundreds of handwritten notes, files and surveillance videos of adult staff brutally beating and restraining minors, discovered in the abandoned facility by Kubler and her fellow traumatized survivors, serve as signed confessions to the level of abuse that went on behind Ivy Ridge’s locked doors.

Katherine Kubler explores a trove of files left behind at Ivy Ridge.

Netflix

Each of the series hour-long episodes examines a different aspect of the program’s horrifying history of abuse — the first two episodes follow the group as they work to compile information to prove that Ivy Ridge was a for-profit facility that was set on brainwashing and humiliating its “students” and the concerned parents who enrolled them.

In the third episode, viewers learn how Ivy Ridge was connected to a much larger network of similar facilities that fell under the umbrella organization of the World Wide Association of Specialty Programs and Schools (WWASP) and how the unregulated, troubled teen industry continues to thrive in a state of corruption.

Breaking news from Canada and around the world

sent to your email, as it happens.

What, exactly, went on at Ivy Ridge?

To the public, Ivy Ridge was sold as a boarding school meant to reform wayward teens.

Parents were told their teens would be expected to follow a series of steps that combined academic education and therapeutic interventions that, if completed successfully, would eventually lead to graduation and release from the program.

However, once the teens arrived at the facility, it became clear that Ivy Ridge was not an educational facility at all. They were told they were no longer allowed to step foot outside and, instead, had to move from building to building via makeshift, enclosed walkways.

They were strip-searched upon intake and assigned a “Hope Buddy” — a fellow program member who was given the task of helping them learn the hundreds of rules they were expected to follow.

The kids at Ivy Ridge were told that they had to obtain points to move up in levels, but if they broke any of the rules they would be deducted points. The most serious infractions led to “interventions” — solitary confinement, starvation and physical attacks from the facility’s largely unqualified and untrained staff.

In terms of education, the teens were assigned bogus classwork via homeschool computer programs, sometimes locked in the facility’s computer lab for hours at a time. Because Ivy Ridge wasn’t a credited education facility, any diplomas that were handed out weren’t recognized by the State of New York, as many of the teens tragically learned later in life when they set out to seek employment.

Many of the facilities used ideas formed by the drug rehabilitation program, Synanon, which was founded in the 1950s by Charles Dederich and went on to become a full-blown cult by the late 1970s.

Among Synanon’s teachings, which were adopted by WWASP’s founder Richard Lichfield in 1998, were a group attack therapy technique that involves reenacting painful, traumatic moments, like a rape or death of a family member and blaming and shaming the victim for what happened.

This group attack therapy took place in Ivy Ridge’s “seminar” sessions every four to six weeks, which were marketed as the “emotional growth” facet of the program but consisted of unrelenting brainwashing and mind control tactics for days at a time. The facilitators would attempt to “break” the teens with humiliation, sleep deprivation, starvation and attack therapy to the point that they would falsely confess to past sins and admit to things they hadn’t done to avoid punishment.

Katherine Kubler and other Ivy Ridge survivors talk about their horrific experience.

Netflix

Trending Now

‘He blocked us’: Man accused in Ottawa homicide changed recently, family says

Can you apply for Canada’s dental plan? Eligibility rules get update

There were two ways to make it out of Ivy Ridge – teens could toil for months and months to accumulate points, complete the seminars and work their way up and out of the program, or a parent could come pick them up. However, contact between the students and parents was limited to one letter per week and, for those in the higher levels, a 15-minute phone call every month. Staff monitored these communications, and if the teens complained or said anything negative about the program, they were harshly punished and set back in the program.

Devastated relationships, destroyed mental health

A good portion of the docuseries explores the splintered relationships between Ivy Ridge’s alumni and the well-intentioned parents who put them there.

The grown-up youths’ testimony reveals lingering feelings of betrayal, but many of the guardians insist to their children that the program and parent seminars, which often encouraged them to shame and humiliate their children, were also designed to brainwash them and limit communication to the point they had no idea how bad things were.

Ivy Ridge has closed its doors.

Netflix

It becomes clear through Kubler’s investigation that Ivy Ridge also preyed upon desperate and anxious mothers and fathers and then lied and indoctrinated them into the program, all in an effort to convince parents that Ivy Ridge was the best place for their teens and that its program was the answer to their prayers, while collecting thousands of dollars per month in tuition.

“I wish I had figured it out really quick but it was terrible mistake and I’m so sorry,” Kubler’s dad apologizes at one point in the docuseries, when she confronts him about why it took 15 months for him to pull her out of Ivy Ridge. “I’m with you on the programs, they manipulate parents. I’m so sorry.”

Katherine Kubler and her father, Ken, pose during happier times.

Netflix

The alumni also discuss their difficulty coping after leaving the program. Many report anxiety attacks, insomnia and complex post-traumatic stress disorder. As they rifle through the abandoned documents at Ivy Ridge, some learn that their intake files were falsified or that they were forced to confess to things in the program’s seminars that never appeared in their files.

The bigger picture

Shockingly, the troubled teen industry and programs similar to the one at Ivy Ridge are still fully operational across the U.S. and considered a lucrative operation, despite being largely unregulated.

While all of the WWASP programs that opened in the last 1990s and early 2000s have been shuttered after a litany of death and allegations of abuse, residential treatment centres, wilderness programs and “therapeutic” boarding schools continue to pop up.

Kubler’s documentary shows that the troubled teen industry remains unchecked in the U.S., with some states even signing into agreements with these programs to help them deal with troubled teens.

In 2020, U.S. socialite Paris Hilton spoke out about the “continuous torture” she faced at the Provo Canyon boarding school, where she spent 11 months as a teen. She said she and other teens in the program were physically abused by staff and claimed that they were sexually abused by staff members who would forcibly “perform medical exams.”

In recent years, alumni from WWASP schools have filed lawsuits against Lichfield. Most have been settled out of court, and Lichfield has counter-sued for defamation on several occasions. To this day, no official charges or convictions have come against him.

In 2013, he provided an emailed statement to the New York Times, denying his involvement in anything to do with abuse at Ivy Ridge and similar schools.

“I wasn’t there, I didn’t abuse or mistreat students, nor did I encourage or direct someone else to do so,” he said. “I provided business services that were non-supervision, care, or treatment services to schools that were independently owned and operated.”

“The Program: Cons, Cults and Kidnappings” is streaming on Netflix.