Raël standing near a model of the Elohim spaceship he says took him to an alien world. Courtesy of Netflix

What if Elohim — a Hebrew term for God — created humanity, just like in Genesis? But what if Elohim actually referred to a race of aliens? What if the land of Israel will, indeed, welcome the revelation with the construction of the Third Temple, but said temple will be a spaceship landing pad and alien embassy? Or what if Yahweh was the father of Jesus, as Christianity teaches, but is, again, not a god so much as a skinny green dude with giant oval eyes who also fathered a prophet who is still living?

These are all teachings of Raël, the aforementioned self-proclaimed prophet, a balding Frenchman with a huge, frizzy corona of wild curls around his gleaming scalp. He’s also, incidentally, really into cloning, which he believes explains Jesus’ resurrection — he was just cloned back to life by the Elohim, and then they took him back into their spaceship.

Collectively, these teachings are known as Raëlianism, and they’re the subject of a new documentary miniseries on Netflix, Rael. It’s named after the prophet, who was born Claude Vorilhon, the son of a Sephardic father, who was in hiding from the Nazis, and a 15-year-old French girl.

Perhaps this background influenced Vorilhon’s later teachings. Raëlisnism is, after all, full of Hebrew terminology, and the movement’s symbol consists of a Star of David with a swastika in the center.

On the other hand, he also had a career as a folk singer, a race car driver and a car journalist before he found his career as a prophet with the publication of his 1974 book, The Book That Tells the Truthabout his encounter with a UFO and the Elohim aboard it.

Rael spends much of its four episodes investigating the biggest scandal of the Raëlians: a claim of successful human cloning. Volilhon taught that the secret to eternal life lay in cloning, so they sought to clone a human baby — and announced they’d done so in 2000, with the supposed birth of a baby named Eve. After much legal pressure, they said Eve was born and lived in Israel, an important point as human cloning is illegal everywhere else the movement has a presence.

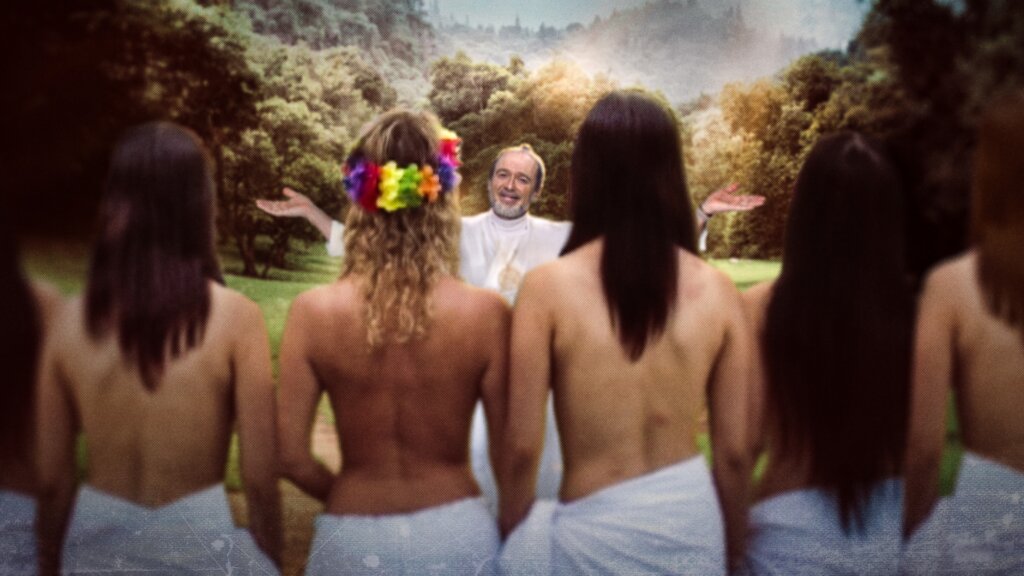

The cloning is a fun curiosity, but the time devoted to the fact that it might be a scam — no one has ever gotten solid proof of Eve’s existence, including the scientist who led the cloning experiment — means that Rael does little interrogating of the philosophy of Raëlianism. Instead, there are plenty of shots of people lying naked and blissed out in the grass during the group’s early free-love days in the late 1970s. It’s a little culty, sure — though the group is technically classified by scholars of religion as a “new religious movement,” not a cult. But it was, after all, the ’70s; free love was everywhere. UFO sightings were also a mainstay of the news at the time.

What sets the movement apart — aside from the cloning — is its philosophy, which strongly echoes Gnosticism and draws heavily from the Bible; Vorilhon cites the plural form of the Hebrew word Elohim as proof that it does not refer to one God but instead many beings — the aliens who created us. He draws on prophecies about the Third Temple to prove that the aliens will return. Sometimes he sings in Hebrew, warbling “Shalom Elohim” as he strums an acoustic guitar like he’s a counselor at summer camp.

Yet Raëlians reject religion. Judaism seems to operate, for them, as a signifier that connotes exoticism but also authenticity — it’s not overly familiar to the French, American and Quebecois people they have largely recruited from, but nevertheless is attached to something that feels ancient. It adds a sense of gravitas and a legitimacy to a group that is otherwise talking about aliens, a topic more associated with tinfoil hats than cosmic truth.

In this way, the Raëlians aren’t operating too differently from several evangelical movements today, who incorporate shofars, tallits and Seders into their new schools of Christianity. After all, who is to say what’s a cult and what’s a religion? The main qualification seems to be surviving the passage of time, and Raëlianism is still operating. Check back in with my clone in a few hundred years.